Disappeared in the GDR: These women doubt the death of their babies

The air is filled with rain as Karin Ranisch gathers with her husband and three daughters at the Trinitatis Cemetery in Dresden. The women stand close to each other while Bernd Ranisch keeps his distance. To his wife and daughters. To the buggers balancing their shovels from the truck, to the whole thing with his son, which took its beginning on a Sunday 43 years ago.

Does my son belong to the stolen children?

The men effortlessly get deeper into the ground - the tomb has been opened and covered two days earlier. The first 60 centimeters are worn away, at 90 centimeters would have to find the remains of a Kindersargs.

The women approach, while Bernd Ranisch steps aside. In his eyes one reads mistrust, maybe even fear. What happens if the undertakers encounter the coffin or even the bones of a child? And what if nothing is found? Nothing of Christoph, who should be buried here and maybe never lay under this earth.

Karin Ranisch, 69, is his mother, a petite woman who wears her hair in a ponytail. She says she has not thought everything through, she only knows one thing: she has to know. She has to find out if her son belongs to the so-called stolen children of the GDR. To those children who are believed to have been declared dead in a hospital for transmission to loyal adoptive parents.

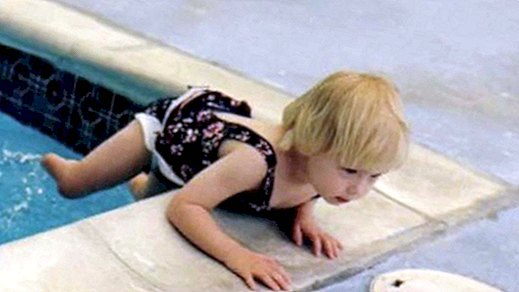

Christoph was two years and four months old when he scalded himself on a Sunday morning in June 1975. "He had pulled the cable of the immersion heater, and the pot fell down on him," says Karin Ranisch. When the ambulance arrived, the doctor said she had seen far worse burns. Also the further course was not disturbing. The parents could see their son at noon through a washer in the hospital, in the evening at 20 o'clock they told them on the phone, he was fine, he had eaten supper. The next morning a telegram lay in her mailbox. It said they had to come.

"We were told that Christoph died, at 9pm the night before, it was such a shock, I remember saying I wanted to see him," recalls Karin Ranisch.

She was told that the child was already in forensic medicine, that she should bring something to wear the next day. "I was looking for a pair of children's tights and a dress shirt, a gift from my sister from the West." Also in Forensic Medicine, we asked if we could see him, only with a petition, it was said It all happened so fast, one day later was the funeral. "

He is not dead. He lives. Maybe in America, who knows.

When she tells of the death of her son Christoph, Karin Ranisch is sitting in her living room with a view over Freital near Dresden. On the sideboard there is a picture frame, in it the photo of a blond curly boy. The Ranischs have not been living here for a long time, they ran a fur business in Hamburg for more than 30 years, they are only recently back home.

"It was maybe two years later when I thought he was not dead. He's alive, maybe in America, who knows," she says. Her forearms are on the table, how much she works in her, you can see them in her hands, which entwine. She smiles sheepishly, she does not know how she gets on America.

The doubts were there, nobody was able to explain to her the death of Christopher, she also did not understand the two death certificates, one from the hospital, which was called "death by scalding", and one from forensic medicine with the statement "death by aspiration", smothered on the stomach contents.

And why did not she say goodbye to her child? It was also common in the GDR that one may see deceased relatives once again. Often there were specially furnished rooms for it.

Until the beginning of last year, says Karin Ranisch, Only her husband was privy to their concerns, but then she came more frequently to reports in the media and turned to the "community of interests stolen children of the GDR," where she met other women who also doubted the death of their children. Some of them, like them, had suddenly lost a well-conceived child in the hospital, others, especially under-age pregnant women, had been told that their child died unexpectedly during or shortly after birth.

What they all had in common was that they had never held a dead child in their arms and had strangely sloppy or very contradictory documents. Death certificates, for example, which were issued in other names and in which one had handwritten registered the own child, missing Autopsieberichte or midwives journals that did not fit the experience. Circumstantial evidence rarely.Little is known about feigned infant deaths yet. There are no secured numbers or finally cleared cases.

Those who did not like the state lost their child

Different with the forced adoption options, These are children who have been pulled out of their families and released for adoption against the wishes of their parents. Often these had been targeted by the state for political reasons, had made themselves punishable by escape attempts, or they were alleged, according to the paragraph 249, the so-called asocial paragraph, to endanger public order. Most of them affected extended families or single women with changing partners or jobs.

A preliminary study concluded that there were at least 400 compulsorily adoped children. Victims' organizations are more likely to be made up of thousands. The "interest group stolen children of the GDR", which attracted attention last year with a petition and an expert hearing, has 1700 members. "There are always more who dare to go public with their story," says Frank Schumann, the spokesman for the organization.

For those affected, it is high time that action is taken. In 2019, when the end of the dictatorship of the GDR reaches its 30th anniversary, hospital records will be released for destruction. "The retention periods are expiring, but they urgently need to be extended," says Schumann. "Parents looking for their child will be made unnecessarily difficult anyway."

After the fall of communism, the compulsory adoption of the GDR was equated with West German adoptions. This means that only the children have the right to information, not the parents. Protecting the children, in the case of forced adoptions, means that mothers and fathers are still exposed to the omnipotence of the authorities.

The midwife untangled the baby and then the doctor grabbed the blanket on our sofa, wrapped it in it and walked away.

Anett Hiermeier from Leipzig knows this impotence, since she was a child. She was seven years old when she witnessed her taking a baby from her mother. "She gave birth to her at home and I was in. It was a pale-skinned girl with black hair that looked like a doll," says the 43-year-old. "The midwife untangled the baby, and then the doctor grabbed the blanket on our sofa, wrapped it in it, and walked away, and I'm behind, walking down the long corridor of our apartment, nobody said a word." Her mother had set up the bassinet the same day. "He had a pink sky, and every day when I came home from school, I was hoping my little sister was in there."

On the thighs of Anett Hiermeier a shoebox with pictures fluctuates. She is looking for photos of her mother, who died in 2007, as she once was, a pretty, cheerful woman, mother of three children, worker in a beverage combine, full time and shift, awarded with bonuses. A normal life of women in the GDR, until February 1983, when it was determined in the sixth month of pregnancy that she expected a severely handicapped child. "Disabled people were not wanted in the GDR, they urged her to abort the child, she refused, and she was threatened with taking away all her other children," says Anett Hiermeier.

It was not long before the state made its threat true. Two months after the birth of the disabled Manuela, the eldest daughter Susanna was picked up and taken to a children's home. In 1984, the following year, the girl with the doll face was born and was released for adoption. In 1985, Uwe, the third-born, was taken to a children's home in Hainewalde, 200 kilometers from Leipzig.

Anett Hiermeier himself came the following year to the Leipzig Children's Home, where her sister already lived. And when her mother was pregnant again, on January 31, 1988, she was also taken this girl. "A child every year, a knife cut every year," says Anett Hiermeier.

The authorities often make the search even more difficult

The separation from her mother reminds her of being traumatic, even though she had nice educators in the home and could look forward to the weekend home. "What was bad was that even as a child I felt that the home was a punishment, I did not have much self-confidence," she says.

The girl of that time has become a woman who laughs often and heartily, likes bright colors, works at the reception of a retirement home and loves to be in contact with other people. "When I started looking for my over-sexed sisters in 2010, some kind of healing started," she says.

The first, older sister Susanna was found surprisingly quickly, because of the fact that the youth welfare office made a request to the adoptive parents, which was received positively by them. Her daughter already knew she was an adopted child.

A year later, Anett Hiermeier again asked the youth welfare office, but it took years before she came to the address of her youngest sister. The authority asked for patience, did not respond to subsequent inquiries and eventually gave the information that the adoptive parents had not responded."I felt ironed out, and others decided on us again," she says.

She also contacted the community of stolen children of the GDR and applied for the file from the hospital where her youngest sister was born. She learned that a family N. from Leipzig had adopted her. She did not get any further, two years passed. Then, in January of last year, she had an idea. She had family photos printed on a red jacket and wore them at a lecture of the syndicate, which she held in Dresden. Tens of thousands saw them on the internet. And then someone sent an address via Facebook.

Anett Hiermeier initially wrote only to the adoptive parents. "We met, and I know now that my sister's name is Claudia. Her parents were sympathetic, no party comrades. We have agreed that Claudia will not learn about her adoption until she finishes her studies. "

Anett Hiermeier looks out the window, where golden yellow autumn leaves dive the backyard in a friendly light. And now? She wants to wait. Maybe one day she'll hug Claudia, maybe they'll never meet. But the most important thing has already happened: she has included the sisters in her biography, in her siblings and her mother's. "I advise everyone to start looking," she says.

Back in the cemetery in Dresden

When the Undertakers Find the First Bone at the Trinitatis Cemetery in Dresden, All of a sudden everyone is confused, one of the daughters of Karin Ranisch takes pictures, but the man from the funeral home dismisses it, false alarm, the bone that has taken on the color of the sand is clearly too big for a two year old child.

In the faces, relief and disappointment are too equal. Renewed silence. Only the shovel clinks as it bumps against the metal grave border. Shortly after a piece of wood comes to light and a rest of black lace. The Undertakers now know that they are digging in the right place and putting things on a white cloth.

The family is approaching, even Bernd Ranisch now bends over the open grave. Daughter Yvonne shudders and turns away in horror as a piece of a sleeve comes to the fore. The eyes of Karin Ranisch swim as she receives the tattered fabric and says, yes, he could come from the shirt that she had given 43 years ago in forensic medicine. The undertakers continue digging and find decayed tights that still show the pattern and some skull bones. Then nothing more. They set the shovels aside and shake their heads. Where are the other bones? Of arms and legs, ribs? There should be more to be found.

And yet, says Karin Ranisch, there is the little shirt, the tights with the pattern. The undertakers begin to shovel the sand back into the grave. The white cloth closes over the finds that will later be sent to a forensic institute. The institute is located in Bonn, emphasizes Karin Ranisch, not in the new federal states. You never know who you meet there.

VIDEO TIP: This child was released for adoption 20 years ago