His last project: An opera house for Africa

Christoph Schlingensief: Pictures of an artist's life

Christoph Schlingensief: Pictures of an artist's life

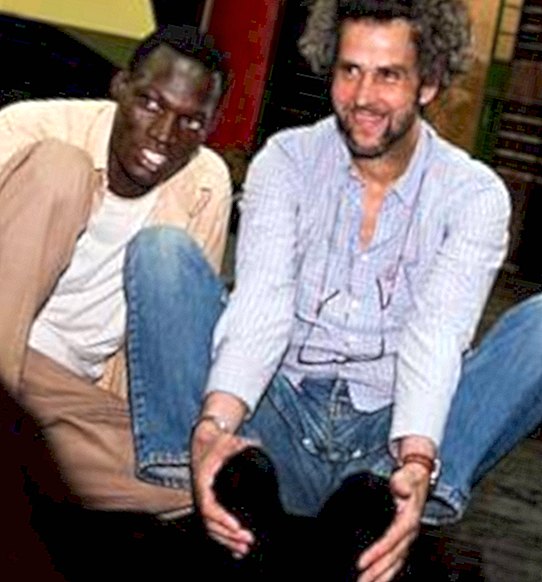

Director Christoph Schlingensief at a meeting with artists who were cast for his opera project.

Like every morning she got up in the dark and woke the girl. Together they stoked the fire: three places next to each other for three heavy galvanized pots. They cooked in silence until the sun stood diagonally over the hovels of the huts: rice, beans, tomato sauce, onions, turmeric, and allspice. The girl ran to get the donkey, which, despite its bound front legs, hopped far out into the savannah. In the meantime, Denise Compaoré filled the food in large, colorful plastic bowls, covered them with colorful cloths and loaded everything into the trolley. Then she tensed the animal. Another slap for the donkey, a word of warning for the daughter. "Watch the money," she says, and as always, the girl just nods wearily.

The girl is gone, the old blind aunt who sits every day in the wall shadow outside the gate calls for food. Denise reboots the fires, the sun is already high, and she is sweating over the flames. Her upper arms are muscular from carrying logs, stirring in large pots. Another six kilos of rice, four kilos of beans, once again stir a pot full of sauce, this time with large pieces of coal. "Mama Denise," the workers said, "put cabbage in the gravy, or we will not eat with you."

Denise Compaore sells food to the workers at the Opera construction site.

The construction site was abandoned for four days. Four days without pay. Yesterday, when she bought the goods for today, she had to ask for credit. She spent seven euros, and if there are not enough hungry workers on the site today and in the following days, she will not be able to pay the sons' tuition this month. They build a school. That's what the workers told her. That white people are there and give orders is in Denise? Homeland, in Burkina Faso, nothing unusual. The West African state is one that is often abbreviated in international reports. A HIPC, which is pretty much in last place in the HDI. One of the Highly Indebted Poor Countries ranked 174 out of 177 on the Human Development Index. You can hardly be poorer anymore.

La Site, the construction site, Denise said to this site. 15 hectares of savannah covered with hard-baked red sand, acacia and sheathing, granite rocks that look like sleeping animals. What is just another development aid project for Denise has been celebrated in Germany for some time as a European-African symbiosis. Here, on a plateau 30 kilometers northeast of the capital Ougadougou, a German theater director, author, filmmaker has an opera, an entire opera village including hospital and school built. Last year, the German feuilleton dreamed of this place, describing an African Arcadia: the perfect backdrop for uniting through art what is separate in reality.

There is no word for Opera House in the language of the people of Burkina Faso.

In Denise? Language, the Mòoré of Mossi, there is no translation for opera. For singing, for dancing, that's fine. But why do you need a house for it, a roof over it, when you can dance in the shade of the thorny acacia and stomp your bare feet into the warm sand? And how can you build a complete village if a village grows over generations and every farmhouse is enlarged by the children and grandchildren?

Denise Compaoré is 53 years old. You do not see her for five decades. She just holds her back, dominated and with smooth skin is her face. Her last name is like that of the President of Burkina Faso: Blaise Compaoré. He is not a close relative, because if he were, Denise would have taken care of it. She would not have to live in this coffin of Tamissi, not on her brother's farm. She still lived in the city and had her little shop. She gave up both the shop and city life when her husband died in a car accident 13 years ago and she was with three children. So she went back to her home village and took what the family gave her.

The people of Tambeyorgo.

By the time the whites came and started building, Denise sold their food at the nearest market, two kilometers away.Only when one truck after another rolled up and colorful huge containers were parked in the middle of the savanna, when they announced in Timissi, looking for construction workers, and the king from his village Tambeyorgo opened and gave the construction project his blessing, Denise realized that opened up a new earning opportunity. From then on, she sent her 14-year-old daughter Mariam to the market, cooked twice in the morning, then washed, tied a clean skirt, and drove her donkey to where the bricks were bobbing in the hot sun.

Tamissi is a quiet place inhabited by 70 families, each in their own huts, surrounded by a wall of mud. The gates are always open, so that everyone can go in and out, including the goats, the donkeys, the cattle, which are the only possible wealth. Money could never be earned in Tamissi, what you need is exchanged. A piece of fabric against ten bricks, a medicine against a straw mat for the roof. Only those who grow more, more corn, sorghum, tomatoes, cassava than he and his people can eat, can sell the surplus on the market for little money.

In the neighboring village of Tambeyorgo, Naba Baongo sits like every other afternoon in the shadow of the north wall of his farmstead. Naba is an honorary title and means as much as king. Naba Baongo has the supremacy over his people and the country where they live. Also about that, which now cultivate the whites with this thing whose meaning he does not understand and into which he will lead his oldest wife Tiendregeogo Tielbaremba to dance when it is finished.

Architect Francis Keré lives in Berlin - and understands every day a bit more, under which pressure the construction project stands.

It was no surprise to Naba Baongo when the whites arrived. His father had told him 76 years ago that something special was going to happen there. And he also wisely advised him what kind of sacrifice he would have to make then. Not a red chicken, because a red chicken means blood, only white chickens could soothe the spirit of this place.

It was in January of this year when the black architect of white men called the kings and chiefs together. "You will make money," Francis Keré had said, and they trusted him because he is one of them, a Mossi. He asked her to give her consent, and he asked Naba Baongo to cleanse the place of all evil. The king did not have to think about it for long. Although he says the whites are not as bright as the Mossi, who had no writing and memory, retaining and passing on every narrative, the whites had power because they had money. Naba Baongo has never heard of the fact that a white man desires something and you can turn it down. He gave his blessing to Tambeyorgo in exchange for a road, water and electricity. He could also have taken money, but having the white men in his debt gives him more room to maneuver. Naba Baongo would like to share in the wealth that the strangers carry into the savannah with their cars and big television cameras, their umbrellas, cigarettes, coca-cans, and their thin public relation women. Naba Baongo has heard as little about public relations as he has about opera. But he knows that rich women become fat and even richer ones thin again, "because they are so saturated with money that they do not need food anymore." If the whites do not live up to their promise, he can summon the spirits again at any time, and then the bricks will crumble, break the foundations, and the workers will crash.

It's eleven o'clock when Denise Compaoré leaves her village with donkey and cart. At her side the young Nadesh Ouedrago, the most beautiful in the village. Twice a day, Nadesh drives to the construction site with metal barrels full of water, her daughter Salesh tied behind her back. Karim, her husband, also found work there. For Nadesh, the site means freedom from the day-to-day duties of being the daughter-in-law of the family. Although she has to give the money, but "no longer do the boring work".

Far, Denise does not drive with her cart. From all sides come the women of Timissi run, plastic and enamel bowls in the hand, even in the poorest homestead, where live the nomadic Peul, the toothless old Salu Dijalu, treat yourself to that day a serving of rice with beans. The sun is already at its zenith when Denise arrives at the construction site. She sets up her bowls under a roof of thick straw mats and wipes the dust out of the tin trays she brought with her hand. Today she sells sardines for seven extra cents, but hardly any of the men has so much money with them.

This is Africa's first opera house, built with mud bricks.

Under another thatched roof, the architect Francis Keré bends over the plans and painstakingly paints the change requests of the client who was visiting. Keré has just flown in from his adopted home of Berlin and wears shirt and jeans from the designer. Next to his supervisor - in his torn shirt and faded pants - he looks like from another world. Only the sweat that runs down his face like all the others.Since he is known as the architect of the director, he finds no peace. TV crews and reporters get on his back. If he had known what was to come, not only about unrest and work, but also about German caprice and pressure, he would never have said yes. The sick builder wants speed, wants to see the walls grow, the workers call for silence, the bricks have to dry, the spirits must not be awakened, the African day has its own rhythm. Soon the rainy season begins, then torrents form on the dry soil until everything is just mud. If all goes well, the private home of the client, the school by the end of the year are ready, where now only dust, foyer and hall are. If everything goes wrong, the drop height for Keré is very high. "I just want to show that I can make operas out of clay, but the world out there craves sensations." As a Burkinabe, Keré has a lot to lose. He is not only responsible to the villagers. Even the ministers of his country, who promise tourism from the festival village and where he sought assistance. Whether he knows the movie "Fitzcarraldo", his friends have asked him and laughed a little compassionately.

What is the intersection between Denise and the whites?

Denise does not know about the ideas that whites use to get out of their air-conditioned cars and blow them across the field as if it were a new wind. The terms from the language of the German educated middle class, the ideological superstructure of the project are difficult to translate into the Mòoré and tell her nothing. The window through which Europe can see Africa and Africa Europe? that's what the client wanted it to be - it's a shoddy one for her. Even if she knew that when the whites leave the hot worksite and head back to the city, they live in hotels that have fans in their backyard spraying cold air and cooling water, it does not appeal to them there's no such thing as her life and that of the whites. Whatever the finished festival house will be? elite self-realization of a man who quarreled with his mortality, or an ambitious artist project that mitigates the futility of youth in the villages - Denise will not be involved either way. When the buildings are finished, the workers move away, and the tourists and cultural workers expected are unlikely to eat their rice with beans.

It is three o'clock when Denise loads her bowls back onto the cart and covers the remains with the cloths. The men have the midday heat in the shade, now the work begins again. Denise counts her coins. She sold 27 food, a good four euros. Only if the daughter has sold well in the market, Denise will be able to cover the seven euro purchase cost that day.

When she is home, after a detour via the nearest market, the sun is already setting. The sons, the brother with his wife and children are happy about the leftovers of the food. Before she goes to bed, Denise brings the battery-powered radio out of her hut and puts it into the son's hand. "Find something they call lópera in French," she tells him. And then they laugh for a long time over the absurd idea that the old junk radio could elicit something with such a complicated name.

The festival village of Laongo

The festival playground of Laongo, as the project is called after the largest village in the area, is an idea of the German theater director Christoph Schlingensief. The artist traveled through Africa in the summer of 2009 to find a place for his idea of building an opera and a school where artistic workshops are also held. In Burkina Faso, he found it and leased 15 hectares of land from the state. In February of this year was the laying of the cornerstone. In addition to the school and the Festspielhaus, there will be a hospital ward, a small hotel and houses for people willing to settle there, including a house for the director. The Festspielhaus is financed by private donations as well as funds from the Federal Foreign Office and German cultural foundations.

Christoph Schlingensief died of cancer on 21 August 2010, shortly before his 50th birthday.