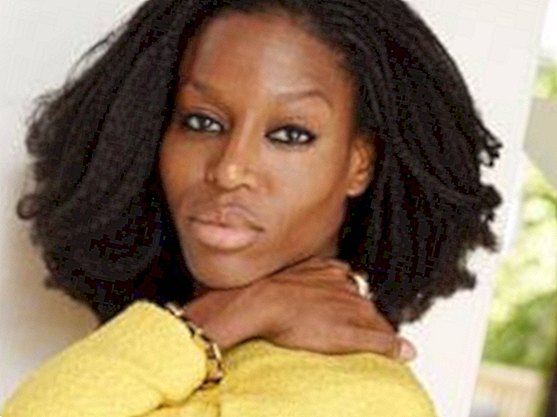

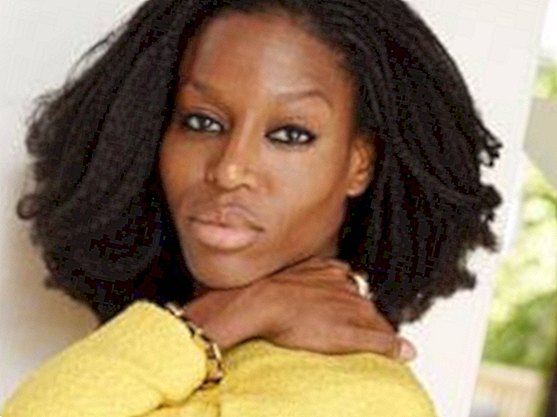

Taiye Selasi: The Afropolitin

At home in many worlds: Taiye Selasi was born in London and grew up in Massachusetts. Her parents, both doctors and civil rights activists, are from Ghana.

© Gaby GersterIn the case of Taiye Selasi, God has kept the watering can filled with beauty, glamor, wisdom, and literary talent for a rather long time over a single person. And we grant her that, because the woman who was born in London and grew up in Massachusetts, the daughter of a Nigerian-Scottish pediatrician and a Ghanaian surgeon, has with her debut "These things do not happen just like that" (more in the current ChroniquesDuVasteMonde Woman) written one of the most beautiful books of the year. A biographically colored novel that is a journey into the heart of an African immigrant family in the US - upper middle class, Yale and Oxford graduates such as Taiye Selasi, doctors, lawyers, artists. Six people who hurt and lose themselves, and only years later reconciliation on African soil succeeds. The novel breaks with force the cliché of the poor African without education and ambition.

An icon of a whole generation of young people with academic degrees and African roots, Taiye, who now lives in New York and Rome, became an essay in the alternative-political "LIP Magazine" in 2005, which later became widely available on the Internet. As a student she described her existence between continents and cultures and invented the term "Afropolitan", which is now used worldwide: "This latest generation of African emigrants is recognizable by the combination of London fashion, New York jargon, African values and academic success not the coolest generation in the world? "

Since then it is even worshiped by famous writers like Salman Rushdie and Toni Morrison. Selasi finds this normal, as does the fact that the muse did not kiss her first after a long pause, but spontaneously in a shower and her book was sold to 15 countries even before it was released. Her mother had preached to her early on that ambition is a must. Since then Taiye Selasi is looking for her role models right at the top. "I'm not as creative as God, but I'll do my best."

Readings: Taiye Selasi on tour in Germany and Switzerland

- 13.04.2013, Berlin, KulturBrauerei

- 14.04.2013, Heidelberg, German-American Institute

- 16.04.2013, Zurich, merchants

- 17.04.2013, Freiburg, Peterhofkeller of the University of Freiburg

- 18.04.2013, Frankfurt, Literaturhaus Frankfurt

- 19.04.2013, Lüneburg, Roy Robson Concept House

- 20.04.2013, Hamburg, Hagenbeck Zoo

- 25.04.2013, Stuttgart, Theaterhaus

Read excerpt from "These Things Do not Just Happen" by Taiye Selasi

Taiye Selasi: "These things do not just happen that way", S. Fischer publishing house, 400 p., 21.99 euros

one Kweku dies barefoot on a Sunday before sunrise, his slippers cowering at the door to the bedroom like dogs. Now he is standing on the threshold between the glass veranda and the garden, wondering if he should go back to get the slippers. He does not pick her up. His second wife, Ama, is sleeping there in the bedroom, lips slightly open, frowning, her hot cheeks looking for a cool spot on the pillow, Kweku does not want to wake her. He would not have made it even if he had tried. She sleeps like a cocoyam. A thing without sense organs. She sleeps like his mother, cut off from the world. The house could be cleared by Nigerians in flip-flops - they could roll right to the door in rusty Russian army tanks, regardless of casualties, as they now do on Victoria Island in Lagos (at least he hears that from his friends, Crude Oil). Kings and cowboys driven to Greater Lagos, this weird sort of Africans: fearless and rich). Ama would gently and blissfully continue to snore, the musical accompaniment of a dream of the dance of the sugar fairy and Tchaikovsky.

She sleeps like a child. He thinks the thought anyway, takes him from the bedroom to the glass veranda; a demonstrative act of caution. A show for himself. He has been doing this for a long time, ever since he left his village, small open-air plays for a one-man audience. Or for two people. For him and his cameraman, the silent-invisible cameraman, who then, many decades ago, ran away with him, secretly, in the dark, even before dawn, the ocean very close. This cameraman who follows him ever since and everywhere. Silently filming his life. Or: the life of the man he wants to be and who he will never become. This scene, a bedroom scene: the empathetic husband.Who makes no noise when he slips out of bed, noiselessly flinging the blanket, putting one foot after the other on the floor and making every effort not to wake his non-awakening wife. Do not get up too fast, otherwise the mattress will move. Very quietly sneaking around the room, silently closing the door. Then as silently along the hall, through the door to the courtyard, where she can not hear him guaranteed. Still on tiptoe. The short, heated passageway from the sleeping tract to the living quarters, where he stops for a moment to admire his house.

It is an ingenious composition, this one-story layout, not particularly original, but functional and, above all, elegantly planned. A simple courtyard in the middle, with a door on each side, to the living quarters, to the Esstrakt, to the large bedroom, to the guest rooms. He scribbled the draft in a hospital cafeteria on a napkin, the third year of his residency, at thirty-one. At forty-eight, he bought the property from a patient from Naples, a wealthy estate agent with links to the mafia and type II diabetes, who had moved to Accra because the city reminds him of Naples in the fifties, he claims (the wealth so close to misery, the fresh sea air so close to the sewage, on the beach stinking people beside stinking poor.) At forty-nine he found a carpenter who was ready to accept the order? the only Ghanaian who did not refuse to build a house with a hole in the middle. This carpenter was seventy, with a green star and six-pack. He worked flawlessly and always alone, and after two years he was done. At fifty-one Kweku brought his things, but found it too calm. At the age of fifty-three, he married for the second time. Elegantly planned. Now he stops at one side of the square, between the doors. Here, the structure is clearly visible, he can see the design and he looks at it, just as the painter looks at a painting or the mother looks at the newborn. Full of confusion and reverence that this thing conceived somewhere in the head or body has made it out into the world and now has a life of its own. Somewhat perplexed. How did it get here, from him to him? (Of course, he knows, by the proper use of the appropriate tools, that applies to the painter, the mother, the amateur architect - but still, it is a miracle to see it so.) His house. His beautiful, functional, elegant house that has appeared to him as a whole, as a total concept, in a single moment, like a fertilized egg that is inexplicably flung out of the darkness and contains a complete genetic code. A logical system. The four quadrants: a bow to symmetry, to his training, to graph paper, to the compass, eternal journey, eternal return, and so forth, a gray courtyard, not green, shiny stone, slates, concrete, a tropical refutation, so to speak. homeland. That is, the home rethought, all lines clear and straight, nothing lush, soft or green. In a single moment. Everything is there. Here and now. Decades later, in a street in Old Adabraka, a decaying suburb of colonial mansions, white stucco, stray dogs. The house is the most beautiful thing he has ever created? except Taiwo, he suddenly thinks. The thought a shock. Whereupon Taiwo himself appears before him? the eyelashes a black thicket, the cheekbones chiseled rock and gems as eyes, their pink lips, the same color as the inside of a conch, impossible impossible, an impossible girl? and his "empathetic husband" scene bothers. Then she dissolves into smoke. The house is the most beautiful thing he ever created alone, he corrected himself. Then he continues the corridor to the living area, through the door into the living room, through the dining room, to the glass veranda and to the threshold. Where he stops.

Two Later in the morning, when it started to snow and the man stopped dying and a dog smelled death, Olu will quickly leave the hospital, turn off his Blackberry, stop the coffee and start crying. He will have no idea how the day started in Ghana, he will be miles and oceans and time zones away (and other types of distances that are harder to overcome, such as broken hearts and anger and petrified pain and all the questions who remained unanswered or unanswered for too long, and generations of father-son silence and shame) as he stirs soymilk into the coffee, in a hospital cafeteria, with a blurry look, no sleep, here and not there. But he will imagine it? his father, there, dead in a garden, a man, healthy, fifty-seven, in remarkably good shape, small-round biceps under the skin of his upper arms, small round belly under his undershirt, a Fruit of the Loom fine-ribbed undershirt, very white on dark brown, plus those ridiculous MC Hammer pants he hates, Olu, and loves kweku? and although he tries (he's a doctor, he knows, he can not stand it when his patients ask him, "What if you're wrong?"), he will not let go of the thought. That the doctors are wrong. That such things do not happen "sometimes". That something happened there.No doctor with his experience and certainly not such an exceptionally good doctor? and you can say whatever you want, but the man was first-rate in his job, even his adversaries admit that, an "artist at the scalpel", a surgeon unparalleled, a Ghanaian Carson and so on? no doctor of this caliber could have overlooked any signs of a slowly developing heart attack. Typical coronary thrombosis. Zero problem. To act quickly. And he would have had enough time, half an hour, and that seems rather understated, after all that Mom tells, thirty minutes to act, to return to "education," as Dr. Soto would say, Olus favorite senior physician, his Xicano home saint. Go through symptoms, make a diagnosis, get up, go indoors, wake up the woman and if the woman can not drive? what can be assumed, she can not read? get behind the wheel and get to safety. And put on slippers, my God. But he did not do anything like that. Nothing went through, created nothing. Only crossed a glass veranda, fell into the grass. For no apparent reason? or for inscrutable reasons that Olu can not foresee and that he can not forgive, condemned to ignorance? his father lay, Kweku Sai, the Great Hope the Ga, the lost son, the lost prodigy, just lay there in his sleeping clothes, doing nothing until the merciless sun rose, less a rising than a rebellion, death the pale gray through the golden sword, while inside the wife opened her eyes and saw the slippers in the door. And because she found that strange, she went looking for him and found him. Dead. An exceptional surgeon. And an ordinary heart attack.

On average, you have forty minutes between the beginning of the attack and death. So even if it's true that such things happen "sometimes," that is, if it's true that healthy hearts "sometimes" cramp, just like out of the blue, like a leg cramp, there is still the question of time. The whole minutes in between. Between the first stitch and the last breath. Especially these moments fascinate Olu, he is obsessed with them, already his whole life, in the youth as an athlete, then later as a doctor. The moments that determine the result. The quiet moments. That torn silence between trigger and action, when thought focuses only on what the moment demands, and the whole world slows down, as if to see what happens. If one acts and the other does not. The moments when it is too late. Not the end itself? those few, desperate and shrill seconds that precede the final beep, or the drawn-out beeping of the zero line? but the silence before it, the interruption of the action, the pause. This break is always there, Olu knows, without exception. The seconds immediately after the pistol starts and the runner stays down or comes up too early. Or after the shot victim senses how the bullet tears his skin, and feels for the wound with his hand or not. The world stands still. Whether the runner wins and whether the patient comes through ultimately has less to do with how he crosses the line than with what he has done in the moments just before. Kweku did not do anything, and Olu does not know why. How could his father not know what was going on? And if he realized, how could he stay there to die? No. Something had to happen that took his bearings, an overwhelming feeling, a mental confusion. Olu does not know what it was. He only knows so much: an active man, under sixty, no known diseases, raised with freshwater fish, running five miles every day, fucking an attractive village idiot? You can say whatever you want, but this new wife is not a nurse. There is no point reproaching, but there might have been hope, the right chest compressions / if she woke up? but such a man does not die of cardiac arrest in a garden. Something must have stopped him.