Safari in Namibia: In the land of big rivers

"Beven, if we're not there by sunset, I'll break your legs," Dusty Rodgers had said, and Beven had nodded steadily. Beven is nature guide, driver, boatman and a few hundred other things more. Rodgers is Bevens Boss, a robber of Irish origin and also a notorious androher of broken bones. Together they are one of those typical Caprivian couples. Occasionally comparable to Derrick and Harry. Or with Petterson and Findus.

Rodgers wanted to reach his lodge "Susuwe" by sunset and said something about Gin Tonic on the treehouse platform overlooking the island and across the Kwando River. This we had already followed the whole day. First by boat, crossing reed islands, past humming Hippo families. Walking under the eyes of large-eyed graceful antelopes. Sometimes we came too close to an elephant standing on the shore, and then, in an antiquarian manner, slapped his ears and killed until Rodgers shouted to him that it was enough, and indeed the animal was trolling. Was probably worried about his legs!

In the afternoon we had switched to the Beven Jeep, which was on the shore somewhere in the middle of nowhere, and Beven said he just wanted to be called Beven. Instead of gasping for the threat of his boss, he drove leisurely across the sand tracks until the sun began its descent. Then he stopped, opened a table, polished the glasses so that the rays of the setting sun caught in them, brought out Biltong, dried wild meat cut into strips. When we hit, the elephants came to drink. Almost noiseless, they moved past us and built themselves up on the shore. They were sipping water, we the gin and tonic, and only when the sun was low, Beven ushered us back into the jeep. Over the now dark roads we bumped to the only light far and wide. "Susuwe," Beven said. Through the cool night air, this word drew like a magical sound. For the last few meters on the island we went back to a boat. The hippos snorted in the dark water, frogs concerted, the moon hung askew, the stars twinkled a thousand times. The lodge lay hidden in the reeds, bathed in candlelight, and almost that moment would have been like a sweet dream of Africa, had Rodgers not said, but finally he would break Beven's legs.

There would have been many destinations for a trip to Namibia. A whole country full of geographical wonders and wild animals. But I really wanted to go to that part of the country that extends like an index finger from Namibia and points to Zimbabwe, Zambia, Botswana and Angola. I wanted to go where rivers flow seamlessly together. Zambezi, Kwando, Okawango, Linyanti. Where the water winds around scrubland and wrests islands, where elephants go their way, without regard to the borders drawn by humans. I wanted to go to Caprivi.

Boats and ferries attract me as long as I can remember. It's something nomadic in me. No matter where I am, I always want to go further: to the other shore, beyond the horizon. Caprivi is fulfilling this idea of moving on, its rivers make it, and the next border, the nearest land is always only a drive away.

Chief Joseph Tembe, whose tribal name is Mayuni, is the head of the Mafwe in Caprivi and a champion of nature conservation

© Andrea JeskaCaprivi is called since 2013 correctly Zambezi region. A name chosen by the Namibian government to drive out the last shadows of the colonial era. The locals continue to say Caprivi. The strip is a geographic anachronism. Named after a German Chancellor, Leo Graf von Caprivi, he was created for one purpose only: so that the colonial rulers of German Southwest Africa, now Namibia, got access to the Sambesi. This is the only reason why this water reed bush finger squeezes across the neighboring states. And only because of its location far from the rest, especially from the tourist destinations of Namibia, it is still a little discovered by tourism wilderness. Until Namibia's independence in 1990, the South African military was stationed there because South Africa's apartheid government had appropriated Namibia. Not even Namibians were allowed to go to Caprivi, and the animals there did not fare well either. The rural population killed her because she needed food or the wild life left trampled fields behind. The soldiers shot them for the same reasons or just for fun. In 1990, when Namibia became independent, Caprivi was a forgotten piece of land without perspective.

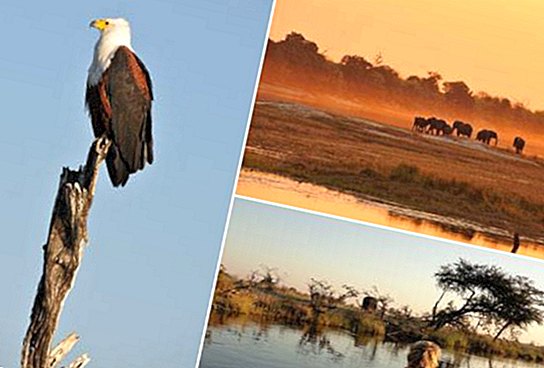

My journey began as a river cruise with a houseboat on the Chobe. Botswana was on the left, Namibia on the right, and in between we sailed as quietly as if someone had turned off the sound of the world. Children played on the riverbank.Fishermen landed in dinghies with their morning catch. They were tilapia perches of considerable size. Water taxis, small metal boats, brought women from the surrounding villages. Ospreys circled, a giraffe drank gracefully with his X-legs bent, and Kudus eyed me with meditative calm. Being in the midst of all that color-tone-smell menagerie produced that gut-feeling of happiness that's like a drug to me. And for that reason I travel to Africa again and again.

In the evening we landed on a sandbank. Cicadas performed, lions roared, the sun sank and cleared the sky for a huge, perfectly rounded moon. I hardly slept that first night. I heard elephants and hippos. The scrubland on both shores screamed and sighed, and stars flashed right into my cabin. I felt like a child who experiences the world as a miracle.

Clear case: elephants are water rats

© iStock / ThinkstockThe next morning the houseboat sailed without me. I got on a motorboat. In the morning sun, I had seen fishermen hide their nets, the drops of water on them had glittered like gems, and suddenly it was impossible for me to leave the river. I wanted to drive and drive, hold on to this glitter and the sky blue.

Maybe Caprivi would have been forgotten, and I would never have gone there. But then the animals came back or were resettled. At first not to the delight of the inhabitants. The lions ate the cattle, the elephants trampled the fields. So how should people have an interest in protecting the new livestock? The Windhoek entrepreneur Rodgers was one of the first to invest in Caprivi and understood that development would not work if people were excluded.

Rodgers made Caprivi his home for a few years, sitting in the Chiefs' huts, hearing what the inhabitants desired and needed to live in peace with the wild animals. "We had to give people an incentive to want to protect the wildlife, which was only possible by providing them with tourism profits, giving them shares in the lodges."

For a long time, the rivers have not been as rich in fish as they once were, but fishing is still taking place from dugout boats.

© Andrea JeskaIn parallel with the private efforts for the region, a great vision germinated and grew. Angola, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Zambia and Namibia decided to create a trans-national nature reserve in which the animals literally have boundless freedom. At the same time, this nature conservation should become the source of income for the population living within the protected area. Conservancies, protected areas that are subordinate to the municipalities, have been staked out, ecological corridors created, the wildlife stock counted. 20 years later, in the summer of 2012, the vision had become reality. The Kavango Zambezi Transfrontier Park, Kaza for short, was opened: at 440,000 square kilometers, it is about the size of Sweden. 36 national parks lie within its borders. Germany has added 35.5 million euros. At the heart of the five-country area, Caprivi has been at the forefront of implementing the project's environmental and social objectives.

I learned the tiger fish roulette story on the third night. We arrived in the Nkasa Lupala National Park by car and again with many boats. Our accommodation was the tent lodge "Casa Lupala", whose comfort made the word "camping" ridiculous and whose location made the rest of the world useless. Reeds, waterways, grunting hippos and elephants, my heart never wanted, never else.

We could not leave that morning because an elephant family was standing around our jeep and was not pleased to respond to our miserable attempts to recapture the car for us. We had to wait until they moved on. Also in the evening they moved through the camp, and we heard their panting and malming, the cracking of the branches. Maybe it was the gin, maybe the stars confused him, at least Rodgers told of his very own Caprivi test of courage: Confident men wrap around ... - guess what - with aluminum foil and then swim through the river. To the delight of tiger fish, which are attracted by everything that flashes. A story that needs no further details, but shows that although Caprivi is Namibia, it has its own laws.

Of course, Dusty did not break Beven's legs. Finally he needs him. When we arrive on "Susuwe", Beven serves us supper. There is pumpkin soup, grilled kudu steaks, young vegetables, South African red wine and for dessert English pudding. Like every evening in this water landscape, where the lungs fill with the best oxygen, I am hungry enough to eat a whole kudu. After dinner we sit around the campfire, take off our shoes and paint figures in the sand with our bare feet. Beven talks about his 16 years of experience with tourists.Once an Englishman has complained about the nocturnal grunting of the hippos, once a Swiss astonished determined that Namibia is no longer German southwest. We laugh a lot, watch the stars with our heads wide, sip our glasses and philosophize about the disadvantages and the wrong ways of life in civilization. "How nice it would be ...", we say. But then we let the sentence hang in the air. We know that it is a romanticizing thought to need no more than this sky, these rivers.

Hippo, be vigilant: A mother protects her babies

© MogensTroll / istockphoto.comAs I walk to my cottage late at night, accompanied by Beven and a flashlight, a hippo runs away with a wobbly butt and plunges into the river in the dark. We hear it splash. Would not that be boring for him? I ask Beven. The stars, the animals, the water, the rest? Somehow it would calm me down, he said yes now. Then my doubts about civilization would be over. But Beven shakes his head, laughs. "Well," I insist, "bush is bush, elephant is elephant, hippo is hippo." Beven looks at me sympathetically. "Not in Caprivi! Caprivi is different every day." I nod. He is right, the boy.

Travel information for Namibia

A complete travel package for Caprivi is to book on "evening sun Africa" (www.abendsonneafrika.de). The trip described here with an overnight stay on the houseboat and then by car and boat through the national parks Mamili, Nkasa Lupala and Bwabata as well as another six nights in the lodges mentioned below costs about 2350 Euro per person in a double room.

flights from Frankfurt to Johannesburg and on to Kasane in Botswana with South African Airways from 1130 Euro, www.flysaa.de.

overnight stay in the "Susuwe Lodge" with full board and all activities per person and night about 330 Euro, www.caprivicollection.com.

In the "Nkasa Lupala Lodge" costs the night in a luxury tent per person per night with double occupancy about 120 euros. Tel. 00264/81/147 77 98, www.nkasalupalalodge.com.

House boats on the Chobe or Linyanti via www.ichobezi.co.za.

Safaris and individual transports in Caprivi are organized by Tutwa Tourism and Travel. Tel. 00264/64/40 40 99, www.tutwatourism.com.

additional Information via the Tourist Office, www.namibia-tourism.com.

For reading: "The Namibia Book - Highlights of a fascinating country", travel guide from Kunth Verlag, 240 p., 24.95 euros

Eleven adventurous reports by Fabian von Poser: "Report Namibia: Through the Eyes of the Cheetah", 132 p., 14.90 euros, Picus